On an unnamed whaler in 1850, Charles Nordhoff and his friend ‘Bill’ boarded the ship that was to be their home for years. Upon passing the captain’s quarters they were surprised to see, scrawled in large chalk letters above the door, “Hezekiah Ellsprett’s berth”. Hezekiah was not the captain, but instead a greenhand who had quite a trick played on him.

When a whaleship first put to sea, men clambered into the ship with their belongings to claim their preferred bunk. Nordhoff discussed Hezekiah’s search, writing “after a deliberate scrutiny of the premises, fore and aft, [he] had arrived at the sage conclusion, that a certain state-room contained more of the elements of comfort, than any other place which had met his eye”. Unsure if such a room was his to claim, Hezekiah asked the ship keeper if it was available to him. The ship keeper, apparently in the mood to do a bit of mischief, wryly told the new sailor that “he had an indisputable right to choose whatever berth suited him best - and advised him for further security to write his name upon the door, and place his bedding in the bunk or standing bed-place -which he immediately did.”

“One can imagine the Captain’s surprise, on coming on board the next day, to find himself a trespasser in his own domain,” Nordhoff wrote. “But words would fail to describe the unaffected look of astonishment displayed in Hezekiah’s sapient countenance, when he was informed that that was ‘not his end of the ship.’”

So, let us begin at the part of the ship that was truly set aside for Hezekiah and his fellows.

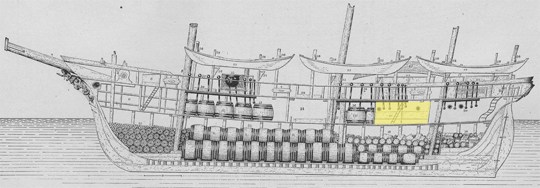

FORECASTLE

The forecastle (fo'c'sle) was the home of the ordinary sailors and greenhands, which on an average whaling crew was often 20-odd men. It was located at the forward part of the ship, where the pitch would be most greatly felt. It was incredibly cramped, lined with bunks and hammocks and, once everyone’s seachests were brought in, very little floor space. Still, this is where men would sleep, eat, and pass their leisure, and would be their enduring home for 3-4 years.

This was the space on the Charles W. Morgan (now located at the Mystic Seaport Museum) that, along with the blubber room, felt most visceral to me when I visited. Despite it being a cold day and my being alone in the space, the humidity and closeness of the air was palpable. But even standing among that network of bunks, the reality of that space couldn’t be fully understood without also bringing back those 20 sailors who shared it, and all the sensory elements their presence entailed. Whalers wrote frequently about the terrible living conditions on their ship, but in my opinion none wrote so grotesquely of his quarters than greenhand William Abbe aboard the Atkins Adams in 1858. He discussed the first night:

“I turned in + spite of the close air of the forecastle I slept soundly for two or three hours — By this time the forecastle was filthy in the extreme. The sick men vomited on the floor and the vomit ran down between the chests or collected in heaps on the floor. To this was added bits of meat and bread—onion skins—spilt coffee—tobacco spittle—forming in all a disgusting compound.”

Even when the seasickness abated, the filth of the forecastle didn’t improve. A year in, he described the olfactory quality of the whalers’ home in his characteristic prose:

“What habits we have? Cleaning our pans with a rinse of coffee or tea in the bucket — wiped off with some chance oakum — coffee bucket sometimes mistaken for slop bucket or — “prodigious” Domine Sampson would swear—for the — barrel—[referencing the communal urine barrel] meat kids [wooden mess tubs] kicking about forecastle, molasses kegs the haunts of the cockroach, our bunks + heads the established homes of vermin of decidedly enterprising genius — hands — faces — + backs in a state of very dirty nature + our clothes patched like a fancy quilt — + still further variegated by the various stains of tar — slush + oil — or not sweetly but strongly redolent of the barrel or the mingled fragrance of lye and oil soap — + lastly the forecastle — unlike Coleridge’s Cologne — filled with a combination of lesser stinks that would defy analysis — but presided over + overpowered by “one grand Monarque” — the audible — sensible — almost visible Mephitis that selects the forecastle for its peculiar abode + the theater of its loudest speeches + the display of its wildest + most fantastic tricks — Bah! What an idea! Personifying a —whew—! My faecal fancy is worse than the forecastle.”

The hygienic challenges experienced in the fo'c'sle took on a particularly gruesome quality compared to other sailing vessels due to the nature of the job. Ultimately, a whale ship was transformed into a massive slaughterhouse and oil refinery. The tryworks to render blubber down was located almost right above the fo'c'sle, and the heat of it when fired up would not only radiate downwards to where everyone had to live, where all that grossness could REALLY simmer, but it would also send all the vermin scampering out of the woodwork and across the bunks and belongings of those men to escape the heat. The blubber room, where large strips of blubber were hacked up into smaller ones, was just outside the threshold of the fo’c’sle. As a result, oil and gore would be tracked all over the ship, and most definitely into the crews quarters as well. It would find its way into every corner of that living space. Men would turn in wearing clothes soaked with it, hands soaked with it, everything they touched becoming tainted with the work.

“Yet strange to say, with all this I could get along quite well.” Abbe wrote. "The Sea air and sea work gives one strange courage and endurance.”

STEERAGE

Moving aft, just through the blubber room, we would find our way to another space set aside for living quarters: steerage.

Steerage was where the boatsteerers—who essentially operated as petty officers—would live. ‘Idlers’, such as the cooper, carpenter, cook, blacksmith, or steward would also call a place in steerage their home. While still a shared space, it didn’t have the same chaos or density of the forecastle, with fewer bunks to a room that were arranged uniformly along the walls rather than in a labyrinth of hanging fabric and seachests.

Still, descriptions of steerage didn’t fare too much better than the fo’c’sle. In 1904, Clifford W. Ashley of maritime fame joined the whaler Sunbeam for part of the voyage. He was there to research for writings and illustrations he was going to make about the work. Even in the final days of the industry, the ships were virtually unchanged from their golden era. The owners of the ship set aside a place for Ashley in steerage, the captain allowed him free use of his own cabin, and suggested that, as far as sleeping was concerned, Ashley ask the Cooper if he might set up a bunk for him in his room.

“The steerage that night was not an inviting place in which to sleep. On a clutter of chests and dunnage the boat-steerers sprawled, drinking, wrangling, smoking.” Ashley wrote. “The floor was littered with rubbish, the walls hung deep with clothing; squalid, congested, filthy; even the glamour of novelty could not disguise the wretchedness of the scene. The floor was wet and slippery, the air smoky and foul; often a bottle was dropped in the passing or an empty one was smashed to the floor. Through it all was an undertone of water bubbling at the ports and a rustle of oilskins swinging to and fro like pendulums from their hooks on the bulkhead. Roaches scurried about the walls. A chimneyless whale-oil lamp guttered in the draft from the booby hatch and cast a fitful light over the jumble of forms sitting on the chests beneath.”

After two nights in steerage Ashley decided to take up the Captain’s suggestion of putting up with the cooper. This was a small room that was once a sail pen located off the steerage quarters, later turned into a small cabin for the cooper and steward. Of this room, Ashley said:

“It was scarcely larger than a good-sized drygoods box, and an average man could not stand erect in it. Here I had a fore-and-aft berth, the upper one. Our only port opened directly into it, and, worse than its leak, the stench from the bilge reeked up through the trap. It was a simple matter after I turned in for the night to span with one hand the distance from my nose to the deck planking. Hard by my head slept Cooper; beneath me slumbered Steward. In the slight floor space remaining reposed our several seachests.”

MATE CABINS

After steerage came the cabins for the mates. Depending on how many there were, a mate might get his own cabin, but between 2nd, 3rd, and 4th mates they were often were shared as well with two bunks to a room.

It’s important to note that, for all the filth of a whaleship, it was still ultimately home at least for as long as the voyage lasted. Some men found these spaces their refuge, such as 2nd mate of the Arnolda, Benjamin Boodry in 1852. Perhaps because he didn’t share a sleeping space with dozens of others, his room became a bulwark of sorts from the whaling life that made him so miserable and homesick.

“all the comfort I take is when I get in my state room shut the doors and think or imagine myself at home or get to reading and then one half of the time my eyes are on the book and my mind is some wher else”

Often his mind turned back to his shore life, and his cabin became a reflective space for that.

“here I set in my state room the door shut and my whole family of Daguerreotypes around me and my Accordion in my hand and I try to imagine myself in old Mattapoisett but it is far from the reality”

CAPTAIN’S STATE-ROOMS

Lastly, we have the best berth aboard: The captain’s cabin. Unlike in the forecastle where men simply ate sitting on their seachests, there was a mess table available in this general area for the Captain and officers. Sometimes boat-steerers and idlers would share this table too, eating in a shift after their superior officers. Sometimes they’d have a second table of their own. In the photo below, the two doors to the left are the rooms for the mates’ berths. The door to the right of those leads on into steerage.

Beyond this, the Captain’s quarters often consisted of a stateroom for sitting, receiving, and working. If his wife was aboard as well, this often also became her domain (though sometimes a captain would build an additional little sitting room for his wife above deck in the hurricane house). Henrietta Deblois, who accompanied her husband on the Merlin in 1856, described some of the pieces in their cabin:

“In the after cabin with have a green Brussels carpet with a tiny red flower sprinkled all over it, a blk walnut sofa, one chair, a small mirror with a gilt frame — over this is the Barometer — at the side of this hangs the thermometer. Under the mirror is a beautiful carved Sofa. A Melodeon, Music books work baskets and bags, give this room quite a home-look.”

When five Japanese fishermen—Fudenojo, Jusuke, Goemon, Toraemon, and Manjiro—were wrecked on the uninhabited island of Tori Shima, they were eventually rescued by an American whaleship called the John Howland. In an 1841 account written by a Japanese scholar interviewing the castaways, of the captain’s quarters they recalled being “brought inside the ship to the captain’s quarters. Here they saw a row of rooms furnished gorgeously enough to serve as a small shrine for Buddha. The rooms looked so dignified that the castaways were awed and could hardly approach them.”

Mary Brewster, who joined her husband on his ship Tiger in 1845, wrote of the ways she tried to brighten up her rooms throughout the voyage.

“William the cabin boy brought a bunch of flowers amongst them Nasturtiums which remind me of my home. If my friends could look in my rooms they would see a large bundle of herbs, Spearmint and balsam which have perfumed the room, several bunches of green grapes.”

Beyond the sitting room was where the captain would sleep, the most private room on the ship. There was also an instance of one captain of the Charles W. Morgan, Thomas Landers, creating a gimballed bed for his wife Lydia when she joined him in 1864. This was done in an effort to make things more comfortable for her and spare her from seasickness. The bed would swing on a gimbal system, thus remaining level no matter how the ship rolled.

The captain also had his own private Head too; no such Barrel which Abbe called to mind in the fo’c’sle or going over the bows.

But for all the room’s privacy, it was still a whaler.

“I am obliged to stop below all the while decks are full, grease and smoke in an abundance and my own apartments often bear some such footmarks but I have it cleaned every morning and Steward scrubs the stairs and cabin. So we keep tolerable clean below,” said Mary Brewster.

Whaling wife Azubah Cash on the ship Columbia in 1850 expressed anxiety over the oil was finding its way down below and edging towards the threshold of their rooms.

“We cannot report ourships [written over ‘ourselves’] clean now and I do not believe she will be very soon for the oil has run between decks as far as the dining room, I hope it will not get in here.”

Charles Nordhoff described it as inescapable regardless of the hierarchy of living conditions:

“From this smell and taste of blubber, raw, boiling, and burning, there is no relief or place of refuge. The cabin, the forecastle, even the mastheads, all are filled with it, and were it possible to get for a moment to clean quarters, one would loathe himself—reeking as everybody is, with oil.”

When I made my pilgrimage to the Charles W. Morgan, there was something profound standing in the last wooden whaler in the world. But she survived all her crews and she survived her industry. The paint is clean, the rooms feel oddly cozy. Superimposing within those beams the lives of everyone who called her home (and the hundreds of other vessels like her now long gone) really takes the space to a different level. Even though so many men were writing about the dreadfulness of it all, their words populate the space that’s now so vacant without them, and truly makes it real.