As this chapter in Going to Weather finds us off the ship and tossed on a swift narrow craft in pursuit of whales, here’s an exploration of some of the tools of the trade. Content Warning for some mention of animal death.

THE WHALEBOAT

“Such was the Yankee whaleboat as it was finally evolved; the most perfect water craft that has ever floated.” - Clifford Ashley, the Yankee Whaler, 1926

A shot from the 1920s silent film Down to the Sea in Ships. A fictional drama that also functioned as part documentary, containing footage of actual whaling processes.

A whaleship typically carried four whaleboats on her davits (named the bow boat, waist boat, larboard boat, and starboard boat), and often one or two spares if a boat was damaged beyond repair. Whaleboats were roughly 28 feet in length and 6.5 feet across at their widest point amidships. Within them sat six men and roughly 1000 pounds worth of whalecraft, all lowering to tangle with the planet’s largest mammals.

Here was the division of labor across those 6 men:

Boatheader: Mate or Captain, who directs the crew, originally steers the boat, and kills the whale after trading places with the boatsteerer.

Boatsteerer: Petty officer who harpoons the whale, and steers after getting fast and trading places with the boatheader.

Bow Oarsman: Usually the most experienced foremast hand, as he managed the line once a whale was fast and led the crew in holding or hauling it when needed.

Midship Oarsman: His oar was often the longest and heaviest to wield, so he had to have a good deal of strength to manage it. The oars could be up to 18 ft in length and weigh 45lbs.

Tub Oarsman: Managed the whale line tubs, mostly making sure they weren’t fouling, and dumped water on them to keep them from burning when they were being pulled by a whale.

After Oarsman: Usually the least experienced member. He’d coil the line that was hauled back into the boat.

Everything about the whaleboat was designed for the hunt. They were lightweight (around 500-600 pounds without the gear), and highly maneuverable. Pointed at both ends, this enabled the craft to quickly move and turn through the water in any direction. This was particularly valuable when a crew needed to immediately back their oars to get out of the way of an angry whale. The hull planks were laid in a combination of carvel and clinker-built. The carvel-build (planks laid end to end to create a smooth seam) allowed the boat to glide more silently through the water to avoid starling wary whales. It still had some clinker-built planks near the keel however. This was designed for if the boat was overturned by a whale and its crew pitched into the water, they could attempt to spare their lives by hanging on to the lip of the seam since the keel was too wide to reach around and get a good grip on otherwise. The bottoms of the boats were usually painted white, pearl, light grey, or light blue, again to blend in with the surrounding water or ice and avoid ‘gallying’ whales.

Whaleboats were fitted with a great deal of equipment—a mast and sail that could be set up when the wind conditions were favorable. Shorter paddles when one wanted to approach a whale more silently without the rattling of the oars. 300 fathoms (1800 ft) of rope coiled in either one tub or split between two. Two active harpoons and a few more spares, and two or three lances that were used to ultimately kill the whale. A bucket to dump water on a smoking whale line, or to bail water that would inevitably find its way into the boat. Wooden drags to serve as an extra weight on the line to further tire out the whale. A knife and a hatchet to cut the line in emergencies. A waif flag with the colors of ones’ ship to mark a dead whale that needed to be left and returned to later for whatever reason. A lantern keg fitted with candles, firestarters, tobacco, pipes, hardtack, and water, in the event that the whale towed the boat miles out of site of the ship. And a compass to find ones’ way back if that happened.

A whaleboat at the New Bedford Whaling Museum filled with items. Note the lances hanging on the far bulwark, and the line tubs in the middle (with very poorly coiled line…)

A whaleboat could reach a top speed of around 5 or 6 miles an hour, though when towing back the dead weight of a 40 ton animal that was reduced to around 1/2 mile an hour. With whaleboats sometimes being towed 20 miles out of sight of their ship, there was an exhausting demand in operating such a craft. Men would pull after whales from morning to night, and if they ultimately ended up killing one, it would be another several hours to reach the ship. Benjamin Boodry, 2nd Mate of the Arnolda in 1853, spoke of how taxing the life was:

“Tuesday Aug 30th 1853. Comes in with fine pleasant weather and calm Middle part employed in drying Bone at 9 saw BHeads [bowheads] lowered [.] at 12 BBoat [bow boat] struck killed took him to the ship cut him in 4 hours and 25 minutes [.] latter part strong breezes and plenty of rain [.] got 3 hours sleep this 24 hours and I guess I shall sleep some.

Wednesday August 31st. Comes in with fine pleasant weather and calm saw BHeads lowered without success chased all day came on board hungry and I am unhappy as a dog and homesick discontented wish I was at home [.] I’d give all that I have got in this ship and run the risk of going naked or starving to death [.] employed boiling.”

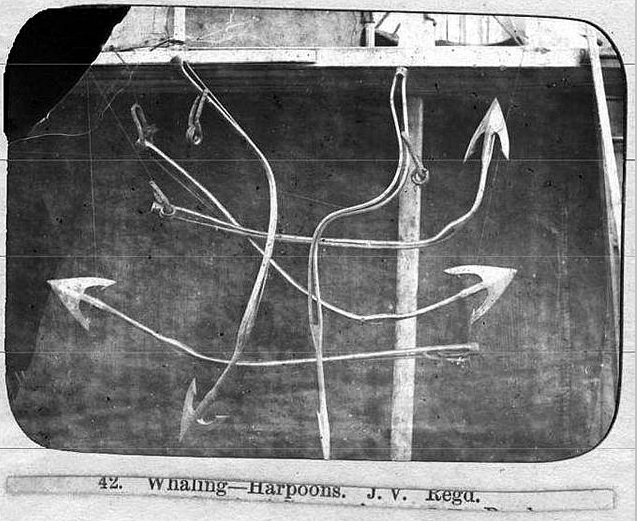

THE HARPOONS

Perhaps the most iconic item out of the industry. This will explore the design of some harpoons used in the U.S. commercial fishery during my very narrow first-half-of-the-19th-c window of focus, with the acknowledgement that they’ve been used for thousands of years by indigenous people all over the world, and the acknowledgement that other forms of 19th/early 20th c harpoons existed in the commercial fishery like bomb lances and harpoon guns. I mustn’t explore those, because this post is getting long enough as it is!

It’s a common misconception that the harpoon was used to kill the whale. Rather, its function was to fasten to a whale to keep it from getting away, and tire it out through dragging 2500-3000lbs worth of men and equipment until it could be hauled up to and killed using a long spear-like object called a lance. Harpoons also weren’t typically thrown as they often wouldn’t have the proper force to successfully puncture very thick blubber. With an iron that measured 2-4ft in length, and the pole they were fitted in measuring another 5 to 6ft, they were quite large objects that weren’t intended to be used at a distance. Instead, they were darted into the whale at the closest possible moment. The term “wood to black skin” spoke to that moment, when the white cedar planks of the whaleboat physically came up against the whale. The driving force of the harpoon was ones’ back hand (the dominant hand) pushing forward to provide most of the power.

Another still from Down to the Sea in Ships, with actor Raymond McKee demonstrating a harpooners stance.

How well a harpoon fastened depended not only on the strength and timing of the boatsteerer, but also on the design of the flues. They went through many iterations in the first half of the 19th century through trial and error.

The earlier harpoons had two flues, first figure. They weren’t the most effective because the two flues meant they often didn’t penetrate into the blubber very well and could draw easier too as the cut made by them was much larger. Then harpoons with a single flue came in–they fastened better without as much force and their shape made it so they also didn’t draw as easily. The last three are toggle harpoons, which were an improvement on both designs. They had a fastening in the toggle that would break under strain once darted into a whale, thus opening the toggle head and creating a T-shape that made a more secure hook. The modern design for the toggle harpoon was created in 1848 by a Black man named Lewis Temple who worked as a blacksmith in New Bedford. He had been inspired by much earlier examples of the toggle technology in Inuit harpoons. It wasn’t ever patented however, so people stole and reproduced his design wildly and it became the standard on whaleships shortly after that. My Historically Inaccurate indulgence is in design work for Going to Weather I like to draw toggle harpoons because they have the most interesting shape, even if they wouldn’t be in usage on commercial whalers yet. Shhhhh.

Harpoons were also usually stamped with the name of the ship they belonged to, as well as the specific whaleboats they equipped (LB for larboard boat, WB for waist boat, etc.). This was largely in the the event that if a whale broke away and died shortly after, the ship crew that killed it could lay claim to it. But I came across one instance in a journal where the crew of the ship Covington on her 1856 voyage tried and successfully skirted around this:

“Early one morning just before sunrise we discovered it [a whale that had been killed by a different ship’s crew] close to us adrift. It not being light enough to be seen from the shore, we lowered away and towed it alongside. We got their irons out as quick as possible and stowed them away out of sight, but had no sooner done so than their boat came alongside claiming it. They were told that they were mistaken, as we had taken it ourselves, but they insisted that it was theirs, and finally the skipper told them that they might wait and see it cut in, and if their irons were found in it they might have the whale, which was a very safe statement on our side, for their irons had been extracted and ours shoved into the places they had occupied. They insisted, notwithstanding, that it was their whale, but in the absence of all positive evidence they were obliged to forego their claim, and left us declaring that they would play us a trick if they ever had a chance, but that chance they never had for the whales that we took were few and far between.”

The blacksmith aboard was often kept busy after a hunt straightening out the irons. When all was said and done, this was what a working iron looked like:

Or, in a particularly wrenching example, this iron at the Peabody Essex Museum truly exemplifies the brutality and horrors of the work, both in the painful strain of the whale’s attempts to free itself, and the power a comparatively feeble man was holding on the end of a line that could end him in an instant.

THE LINE

The terror of the work is in no way complete without speaking of the whale line attached to the harpoon. I love coiling line, myself, and there’s a meditative appeal to the idea of spending a morning carefully laying 225-300 fathoms in a big tub. I mean, look how satisfying:

But the reality of why that line had to be coiled so carefully over so many hours in preparation for its usage really sets my heart in my throat. Every time I look at line tubs situated in exhibits of whaleboats I can’t help but feel a little sense of panic about them. Because the line fouling could very easily kill or maul someone instantaneously while engaged (or, at the very least lead to a boat having to cut free from a whale) there were extra steps taken before it was coiled in the tub to try to prevent that. Once enough new line for the tub was spliced together, it was coiled backwards to start to take out the turns, sometimes several times. Sometimes it was stretched around the bitts by several men to get the kinks out. Other times it was towed behind the ship for a bit first to straighten it out. Then a working coil was made again. Then it was passed through a block aloft, and carefully flemish coiled down in the tub (layers of flemish coil were the only way to get the density needed to fit that much line in a single tub). While it was being coiled, the assistant pulling the the line through the block was further twisting out any of the remaining stress in it as he fed it down. For all that it’d still end up fouling at times.

The tub–sometimes 3ft in diameter–was brought into the whaleboat. The line was first carried aft and turns were put around a bitt or loggerhead at the stern to slow how fast it would pay out once attached to a whale. Then the line was carried up the center to the bow, brought through a lead-brushed groove or ‘chock’, and held there with a slender pin of oak or whalebone to keep the line from jumping out of place and sweeping the boat. 10-20 fathoms of the line was coiled at the bow to have some slack to work with before being attached to the harpoons. The first active harpoon was tied to the main line, and the second active harpoon had a short warp of its own that was also tied to the main line, after going through what usually-verbose Herman Melville described as 'sundry mystifications too tedious to detail’.

This illustration shows a good view of the arrangement. There was also an eye splice hanging out of the tub in the event that the main line was almost payed out, so as to quickly attach another line to it either from a second whaleboat or--in the 2nd half of the 19th century--a smaller spare line tub also located in the boat. At any moment someone was also ready with a hatchet to cut the line and lose the whale, should anything happen that would imperil the crew, such as the line fouling.

But the line--just by its nature--was always a potential death sentence. This photograph shows how close it sat between the men at the oars, and what a small margin of space one had available to avoid it as it ran.

Photograph taken by William Tripp of whaler Philip Gomes, who was a boatsteerer on the bark Wanderer.

Once the harpoon was fast and the line was engaged, that lank rope became a tremendous hazard. As Melville described,

"When the line is darting out, to be seated then in the boat, is like being seated in the midst of the manifold whizzings of a steam-engine in full play, when every flying beam, and shaft, and wheel, is grazing you. It is worse; for you cannot sit motionless in the heart of these perils, because the boat is rocking like a cradle, and you are pitched one way and the other, without the slightest warning"

Even with the turns around the loggerhead the line ran so fast it had to be continuously wet to keep from smoking and setting fire to the whaleboat or burning through itself and parting. And if any man had the misfortune of getting caught in it, he could be taken out of the boat in an instant and drowned, as numerous reports from voyages attested to.

Footage from Down to the Sea In Ships of a fast line paying out while someone splashes water on it off camera.

Such a serene looking neatly coiled tub, and such an object of hazard and potential death to all parties, man and whale. And that is what I bear in mind with each of these objects. That the very shape of them was built on someone’s death. For the successful designs, the death of whales. For the innovations and advancements in the structure of the boats, the death of men who didn’t have those modifications to save them.