As an 1843 voyage, the path of the Valor would never broach the Arctic, still hoping to find success in the South Pacific. However, after 1848 when the commercial whaling fleet learned of bowheads, it pushed northwards in pursuit of them as the old whaling grounds were increasingly overfished.

A struck bowhead whale drawn by Captain Benjamin Boodry.

An anonymous letter published in the Quaker newspaper The Friend in 1850, written from the perspective of a Bowhead whale, offered up a rare perspective in opposition to the industry at this time:

“Although our situation, and that of our neighbors in the Arctic is remote from our enemy’s country, yet we have been knowing to the progress of affairs in the Japan and Ochotsk seas, the Atlantic and Indian oceans, and all the other “whaling grounds”. We have imagined that we were safe in these cold regions; but no; within these last two years a furious attack has been made upon us, an attack more deadly and bloody than any of our race ver experienced in any part of the world. I scorn to speak of the cruelty that has been practiced by our blood-thirsty enemies, armed with harpoon and lance; no age or sex has been spared.”

The expansion was both a detriment to the whales and a detriment to the men who hunted them. Many whalers were ill-prepared for the colder conditions, with often inadequate outfits purchased from the ship’s slop chest. Cases of scurvy (and death from such) increased significantly as months were spent in regions where the resupply of fresh produce wasn’t possible as it was in the South Pacific. The US Consul in Honolulu frequently commented on the condition of the men filling their hospital from a season up North, describing whalers who “died after reaching port and before they could be landed, while others were carried to the hospital on litters, being too feeble to walk.”

The whaling Bark Samboul, 1886. Via New Bedford Whaling Museum.

It also could be a psychologically bleak time as well. Allen Newman, captain of the Covington (1852-55, and 56-59) wrote:

“All this day a strong gale from the East with thick rainy weather, this is hard if I was alone I think I should be tempted to some rash act, such as Murder or Suicide, but I am surrounded with A plenty as poor as myself, misery loves company.”

Later he wished for all the things he couldn’t have access to while bound up in fog and ice.

“hard gale from the North with cold Weather & A Bad Sea such is life on the Ocean. I Wish myself at Home with my Wife & Children, seated by A good fire & eating apples or I would willingly go Without the apples to be there O Lord watch over us keep us in health & give us Prosperity as the years rool round.. I hope to find myself with my family on some May morning & enjoying all the Blessings of A Happy Home.”

Benjamin Boodry, 2nd mate of the Arnolda (1852-55) also missed home after a failed attempt to catch Bowheads.

“Saw B[ow]Heads lowered without success chased all day came on board hungry and I am unhappy as a dog and homesick discontented wish I was at home I’d give all that I have got in the ship and run the risk of going naked or starving to death”

It wasn’t all misery, however. William Stetson, cabin-boy-to-foremast-hand on the Arab (1853-57) talked about some of the fun they had, too.

“We saw several bowheads but could get no where near them, and then all three boats penetrated farther into the ice, our boats crew all got out on a large cake of ice which was covered with snow, and enjoyed a little game of snow ball. To set foot anywhere out of the ship or boat soon on an ice cake in the Kamtschatka sea is very agreeable for a change; we enjoy ourselves among the ice, chasing seals and birds, snow balling, &c.”

Bowheads, with their battering ram heads designed to break through thick ice, knew their world far better than the new predators that just entered into it. In all instances, when pursued, they would make their escape attempt by running under the ice.

“Our officers were not very anxious to tackle them in the ice, as it needs an expert whaleman to handle them there,” wrote Albert Peck, greenhand on the Covington, the same voyage in which his captain was privately contemplating Murder And/Or Suicide and dreaming about home and hearths and apples.

“As soon as one is struck he instantly makes for the compact ice and if he runs under, they are obliged to give him line til they can get the boat clear, and it often happens that before the boat can be cleared the line is gone, it being useless to try to hold it. Sometimes when he is running and they are holding on to the line […] it will strike with its full force against a cake of ice, and if not very large and struck fairly with her stern, it will split and the boat will go between the pieces, but if not struck fairly then wo[e] to the boat. Often times the line will be cut or chaffed off against the ice, and then farewell Mr. Whale.”

Whaling wife Mary Lawrence on board the Addison (1856-60) described such a hunt, and the improvising whalers did when a whale ran under the ice.

“Our boats had not been down more than ten minutes before the whale came up between our bow boat and a boat from another ship. They both started for him, but our boat, having the best chance, struck. He ran under the ice soon after they fastened, but our brave crew were not going to give him up so, so two boats went around the other side of the ice to lance him and send him back, which they finally did after having quite an exciting time. Mr. Nickerson got out of his boat and went on to the ice to try to shoot him, while another boats crew from another ship landed and snowballed the whale, probably wounding him severely.”

The whale was ultimately killed by all this and brought alongside.

Bark Jacob A. Howland, trying out blubber among the ice. 1887. NBWM.

Benjamin Boodry, for all his misery as a 2nd mate on the Arnolda, would find himself up in the ice again as captain on his next voyage aboard the Fanny (1856-60). In icy regions he often described whaling happening in a ‘pond hole’, meaning a section of open water amidst all the ice floes. From the safety of said pond hole, he saw the peril that came with whaling in the Arctic.

“Comes in with light gales from East ship in a pond hole boiling with the Roman [another whaleship] thick and plenty of snow and verry heavy swell at ½ past 7 came to the N side of the pond hole it lighted some saw the wreck of a vessel about 2 miles in the Ice dismasted and the ship Brutus lying by her the swell being to heavy dare not venture through the Ice as the Brutus was there to render all assistence in saveng life poor fellows I pitty them God only knows whose turn it will be next this is a dangerous way of getting an honest living at 8 saw a large light set supposed to be on board of the wreck I wonder what poor fellow it is Middle and latter part blowing spoke Capt Henry of the Brutus haveing Capt Sherman and crew of Bark Newton on board there vessel being stove in the Ice he belongs in Rochester town and has lost his wife since he sailed and now has lost his vessel take my vessel but save me my Little Mary”

Getting wrecked by ice was the greatest risk in the region. At one point the Addison found itself almost entirely bound up in ice, and Mary described the anxiety of the scene.

“The first flow of ice that came to us was not bad, quite thick but considerably broken up. After that it came on pretty bad. We were obliged to have men out on the ice cutting our way along, until we came to a field that was impossible to get through. Just then there came on a slight breeze, so that we slipped out anchor, and turning around a little, we cleared all of that except the point. Then we put down our large anchor and drifted through the remainder, some of which was very heavy, solid field ice two miles in length. After cutting, spading, sawing, and pulling with ropes, we finally worked through the last of it about four o’clock in the morning. It was a night of hard work and anxiety. We were afraid mostly of staving our ship again. There was also danger of dragging our anchor and going ashore.”

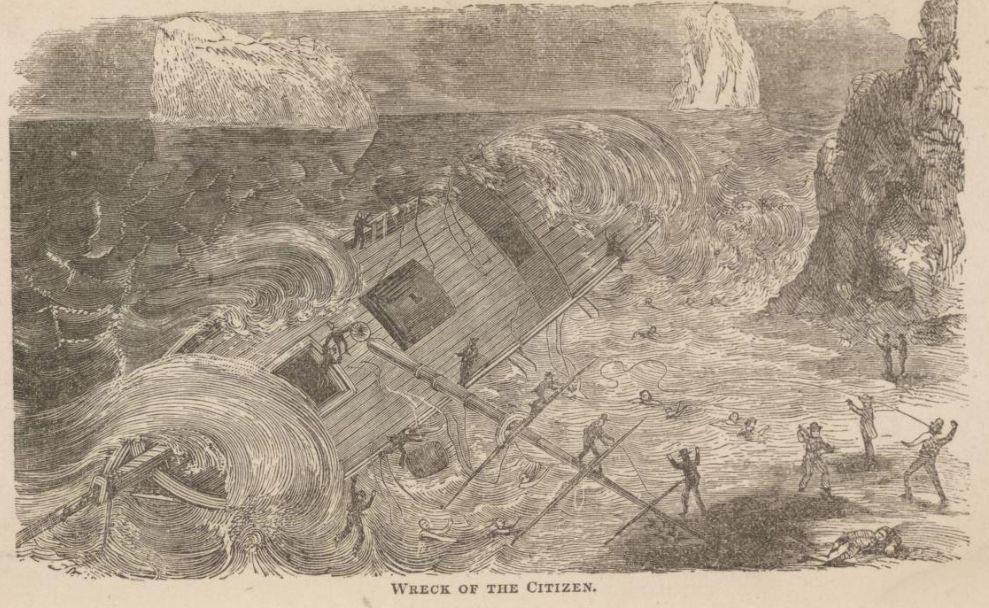

Thomas Howes Norton, captain of the whaleship the Citizen (1852), found his ship less fortunate in navigating the ice.

“Ice was all around us, which would have passed us on the larboard bow, and thus we should have escaped a concussion; but instead of doing this he put the wheel down, which brought the ship into the wind and the consequence was a large hole was stoven in her larboard bow; the ship began to leak badly. Casks were immediately filled with water, and placed on the starboard side of the ship, and thus in a measure heeled the ship, which brought the leak to a considerable extent out of the water; otherwise she must have sunk in a very little time.”

While the crew of the Citizen would patch the damage made on that instance, it wouldn’t help them for long. Their ship would be utterly destroyed in a gale in the Arctic Ocean in September 1852, with five lives lost and thirty-three men stranded ashore with little to protect them.

Wreck of the Citizen, via Library of Congress.

While stranded, those thirty-three men were assisted by the local Yupik people and lived with them for nine months before eventually being brought home by two New England whalers.

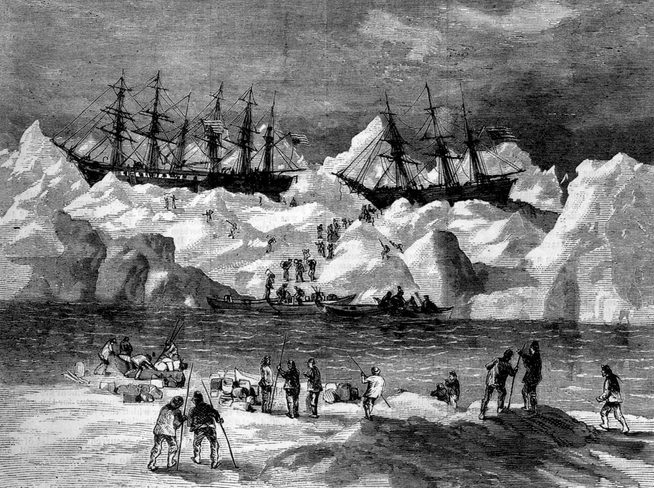

It was the Arctic that played a huge role in finishing the American whale fishery, too. In 1871, thirty-three American whaling vessels were unexpectedly bound up in pack ice off Alaska. Their collective crews (and families aboard) reflected 1219 lives suddenly plunged into mortal peril. All the captains came together and signed a statement of what they all agreed to do:

“We, the undersigned, masters of whaleships now lying at Point Belcher, after holding a meeting concerning our dreadful situation, have all come to the conclusion that our ships cannot be got out this year, and there being no harbor that we can get our vessels into, and not having provisions enough to feed our crews to exceed three months, and being in a barren country, where there is neither food nor fuel to be obtained, we feel ourselves under the painful necessity of abandoning our vessels, and trying to work our way south with our boats, and, if possible, get on board of ships that south of the ice.”

They set their ensigns upside-down, took to their whaleboats, and abandoned the whole endeavor to the Arctic.

Image from Harpers Weekly 1871, of some of the whaleships bound up in ice and the crews evacuating.

Through heavy swells and ice they rowed, hoping to make it to open water where other ships from the fleet might be there to save them. It took them near 90 miles to reach the rest of the fleet, who readily brought them all aboard and returned everyone home at the expense of their own voyages. Remarkably, not a single life was lost in this event. But all but one of the trapped whaleships were crushed by the ice. With the industry already staggered by the discovery of petroleum and by losses during the Civil War when Confederate raiders made a point to target the whaling fleet, this massive loss was the final nail in the coffin for American whaling. Beyond that event, wrecking in the ice became a fate for many a whaleship in the last couple decades of the 19th century.