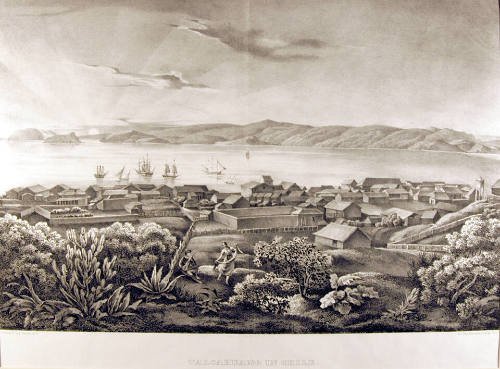

“The principal thoroughfares christened probably by “Jack” go altogether by such names as jib-boom street, fly-jib-boom street, spanker-boom street, &c. These streets are lined with drinking houses and dance houses, and these are generally found crowded with clean shirted sailors and handsome señoritas, stepping off a lively measure to the sound of the violin. Of fruits, peaches, pears, figs, grapes and mostly all such fruits as are found in the New England states abound in profusion, and are to be obtained for very reasonable prices, we happen to be here in about the right season for these luxuries and four months at sea sharpens the appetite for such things remarkably. With all these combined advantages, anyone that could not come ashore and enjoy himself here after being tied up in a whale ship several months need blame himself only.”

-Whaler William Stetson, describing Talcahuno, 1850s

In Going to Weather, Ezra and Josué get a rare few hours to explore the port of Faial, though the other members of the crew get no such privilege this time around. Whalers typically were permitted shore leave infrequently, with often half a year or more stretching on before such a time came. When it did, they were ashore for only a few days at the maximum because:

1) Whaleships would only go to port when absolutely necessary for provisions, captains updating their agents and picking up mail, conducting repairs, or hiring crew—shore leave delays the voyage.

2) In addition to delaying the voyage, ships had to pay harbor fees if they wanted to anchor so many times provisions would just be rowed up to the ship instead.

3) Liberty ashore gives crew the opportunity to desert, attempts at which would inevitably happen almost every time a ship came to port. It also makes it easier for disgruntled whalers to hold work stoppages in the hopes of addressing grievances, as the ship can’t sail again without their labor.

Sometimes captains were met with great resistance over not permitting men to go ashore. This ranged from whalers collectively deciding to refuse to work until leave was granted, to, in one 1843 instance on the Ship Maine, a steward attempting to kill the captain in his sleep with a hatchet for not being given leave (a report which must be taken with a grain of salt, as that was the captain’s words as to why there was an attempt on his life)

Samuel Wood of the Bowditch described the captain as ‘devilish ugly’ for not permitting the crew shore leave when they stopped to repair the ship at Rio de Janeiro in 1849. He lamented about it a number of times in his journal.

“this afternon lowerd one boat and pulled the capt ashoar to Stop for the night but we poor Sailers Stop abourd this is the way Sailors live damn thear eyes & devil take thear soules that my best wish for them great times. […] Sunday this day lying on bourd doing nothing the same as yeasterday [.] we hav good chance to look ashoar but as for geting ashoar the devil mite as wel break the gates of hell and get into heven as the crew of a dam whaler to get ashoard bad luck to them.”

As a general statement, whalers could be a scourge in the communities they stopped in. The business of whaleships was welcome in such ports because the economies became so linked to their presence, but the whalers themselves could cause havoc in the few days they occupied the land. This was largely due to the dynamics of the crew and the lifestyle aboard: a bunch of young 18, 19, 20-something year old men are let loose for a few days liberty after months on an often heavily-disciplined ship. Many of them have the twin goals of get drunk, have sex. Some of them who had tensions boiling on the ship are ready to beat each other up and settle scores the moment they hit land, where it’s harder for officers to witness and punish such behavior. They’re in a foreign port that they likely won’t return to again or at least not for a long stretch of time, so there’s a sense that they can behave however they want with no repercussions. Adding to this, many of the populations where whaleships stopped largely consisted of people of color that white whalers tended to look upon with a range of entitlement / superiority / fetishization / contempt. It certainly created a climate for abusive behavior.

Allen Newman, when he was first mate of the Bowditch in the late 1840s, made very matter-of-fact commentary regarding who got themselves put in the local prison at every shore leave. A few examples:

“Ship ready for Sea and Waiting permit from the Custom House, Peterson and Davis still in Prison, Sylvester Littlefield came on Board Drunk and Abusive, had to force him below to his bunk.

——

Paul Ripple in prison on shore put in for riotous conduct on shore & William Steere has staid over his liberty the past 24 hours.

——

No work on board Sunday, the Larboard Watch on Liberty, Edward Saunders belonging to the Starboard Watch has not returned on board and it is reported that he is in Prison.”

When Newman became captain of the Covington for her 1856 voyage, he was far more candid in his frustrations over his crew’s behavior:

“Sunday 12th Strong trades from the East all day at 7:30 the watch went on shore to have their Drunk and at 6:30 the returned with the Exception of 3 have got Drunk & fell down in it I hope they will Die their I suppose that their is more Drunkards on Board the Covington than any other Ship in the Pacific Ocean it will require more than one Father Mathew to reform them.

Spending time in the local jail wasn’t too much of a deterrent for being rowdy. Cabin boy William Stetson, on the Arab in 1853 commented on this, saying:

“…they have no care on this score; if they get imprisoned they well know their captain will have to take them out before the ship sails and therefore rest easy and contented; even in the calaboose they enjoy themselves, all being in a yard together and therefore the more prisoners the merrier times they have.”

Albert Peck, greenhand on the Covington (mid 1850s), wrote about how he observed his fellow crewmates flat out stealing from vendors in Hakodate:

“This being the last day that we expected to be allowed on shore, towards night the most of us began taking anything they had a fancy for, and getting hold of some sake were soon ready for anything, and going up and down the streets began to take whatever they came across, until the storekeepers becoming alarmed when they saw them coming would take what they had exposed outside and carry it inside for safety. This was kept up until time to go on board, when we marched down to the boats with our booty. As for my own part, I was sorry to see this going on as it tended to create an increased distrust of us, and would detract from the good opinion they had begun to entertain towards us.”

William Stetson described a similar dynamic in whaling ports, with poor behavior also extending to the mates.

“Talcahuano is a poor place for moralizing of this sort, especially when ashore among fifteen or twenty ship crews and every possible inducement offered to go in “with the crowd”. This state of things is not by any means confined to foremast hands alone. The officers are not a whit behind them, and frequently from having a better opportunity from the advance; while ashore on liberty one day I observed a lot of them somewhat ‘elevated’ in a public house, standing before the bar throwing empty bottles at the full ones that were ranged on the shelves behind it: the one breaking the greatest number was the best fellow. Repeat it, “such is life.”

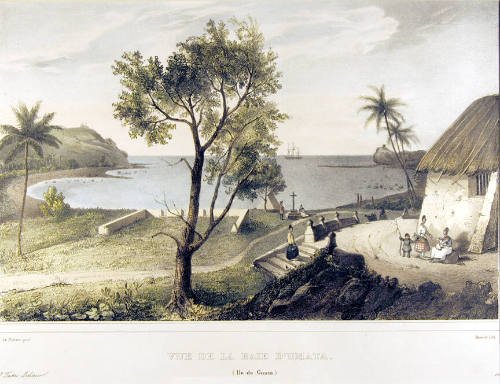

Painting of Guam in the 1830s, by Louis Auguste de Sainson

Interactions between whalers and locals weren’t always antagonistic—Albert also mentioned an instance in Guam that had more camaraderie (but still involved alcohol)

”Having our fiddler with us, we went from one hut to another giving them a tune at each, which would please them very much, and to show their appreciation of it they would produce a bottle of aquadiente [Aguardiente] or brandy, and treat us to a glass which would consist of a coconut shell, until it became evident that this would not do if we intended to walk to the town, as before long we should be incapable of walking anywhere. So we started for the town.”

Another example of charming interactions with locals came from William Abbe’s visit to the Juan Fernandez Islands where in addition to sightseeing, he just played with some local kids and dogs and a man’s donkey.

“3 little fellows hardly knee high to a grasshopper were frolicking about — handsome bright eyed little fellows full of fun — I was soon on the best of terms with them — + they caught me several times with lassos made of raw hide — + which they threw with wonderful skill for children so young— the oldest not about 5 years old — catching me about the neck — I frolicked with them + with some fine looking hounds + at last a man coming down the hill on a jackass — I managed to persuade him to let me have a ride — + mounting my charger like Don Quixote I sallied forth for adventure — I don’t know that I sallied forth — indeed I am confident that I didn’t for that expression is rather too much of brisk movement + quick steps.”

Illustration of Alexander Selkirk, stranded sailor in the Juan Fernandez Islands who’s story inspired the tale of Robinson Crusoe.

Abbe also spent the day exploring and appreciating the natural landscape of the islands, saying, “I have not spent a pleasanter day than I spent on Robinson Crusoe’s Isle […] I picked some ferns from the caves at the isle + some flowers + there with some stones are the mementoes of my Juan Fernandez visit.”

J. Haviland, aboard the Baltic in the 1850s, approached his shore leave seeking the simplest of pleasures, denied at sea. Fresh fruit:

“Lahina [Lahaina] is quite pretty kind of place the streets and land are regular and well lined with large shady trees. They need them for it is the hottist place I ever saw. You cannot look in any directing but what you see fruits in an minese [immense] quantites. I have eaten so much I expect it will make me sick […] Watermellons. Bananas. Oranges. +c. have done them too much. The best mellons I ever tasted I have eaten here […] I have taken 3 messes and don’t want anymore.”

He later made the same mistake gorging himself on too much fruit on another visit off Aitutaki, experiencing the Bromelain in pineapples with much regret: “Nearly Dead calm. My mouth is very sore eating so many Pine Apples.”

For Haviland, stopping in port also meant reconnecting with home, in the hopes of receiving letters from his family.

“I want to get in and hear from Home once more it seems an age since I got a letter from my mother. How many tender recollections that word calls up. Alas what if I should have no mother now. How will I remember the last time I saw her. Methinks I can see her now as I did then when she handed me my Carpet Bag and bid me farewell. I little thought then I should ever be in this part of the World. But man proposses and God Disposses […]

Liberty ashore also meant opportunities to meet with other crews of whaleships. Stetson described several of these. At Talcahuano, a community sweet potato roast went poorly for one drunk fellow:

‘This was at the extreme point where there are but one or two small shanties erected merely as a market place, and here the sailors on that night most did congregate. A quantity of sweet potatoes were handy to us, and monopolizing the fire of the native family, which was burning on the sand, each individual employed himself in roasting sweet potatoes; aguardiente, somehow or other, no body seemed to know how, was continually being passed around the social crowd encircling the fire, and for some time each succeeding passage of the bottle rendered the circle still more social; roasted potatoes were in great demand, and those that put the most in the fire were far from being sure of the largest roasted number; one of the Rousseau’s crowd, a “Pat” suffered in this particular more than any other one of us, and as the soothing influence of the aguardiente began to gradually steal over him he found it very difficult to keep the run of his potato, and was continually making inquiries respecting it; when at last completely overcome by the aguardiente he rolled back in the sand the words “where me po-ta-ty” were trembling on his lips.”

In Lahaina, Stetson’s crew met with another who had a talented member to engage them and the locals with his ventriloquism skills:

“In the evening, Monday, a part of us paid another visit to the Kutusoffs crew and this time had a sober and very agreeable gam. Music and dancing, as on a former occasion, formed a part of the evening’s entertainment, and to this was added a touch of ventriloquism by one of the foremast hands of the K. The ventriloquist gave his representations admirably well, although he had practiced so little lately, he said, that they were given with some difficulty. The crew say that he occasionally affords them much amusement at sea by his gift […] Watches were ashore on liberty from the Liverpool and Kutusoff and with the crew of the latter we had quite a “time”. At “Uncle Henry’s” a display of ventriloquism was exhibited by the “professor” of the Kutusoff and the natives who had probably never seen the like before were somewhat startled to hear a voice proceeding out from under an empty cigar box.”

Painting of the Kutusoff, 19th c. by Benjamin Russell.

Predictably, in larger ports, public houses, brothels, and dance halls were popular destinations. Thomas Nickerson of the Essex spoke of one dance house while ashore in Talcahuano:

”There we found a few young women seated around the hall on wooden stools, and playing off some Spanish airs upon their guitars to dance by. There did not seem to be either melody or music in their touch, but after such an interval of confinement our men were ready to dance to anything had it even been a corn stalk fiddle. With their guitars were an accompaniment of an old copper pan used as a tambourine. To this music did our men dance apparently with as much satisfaction as though it had been the finest music in the world.”

Nickerson however passed judgement on both the women at the dance hall and his crewmates who were “clear of their cash before noon by frequently treating their partner and paying their fiddler”, and aimed to spend his time ashore elsewhere.

“There was a young man in the watch with me who like myself did not much relish this kind of amusement. We therefore agreed to take a stroll up into the country. We therefore left this den of infamy and vice, and started for the mountains. Here having gained the top of a high hill which gave a commanding view of the whole town and a large space of the surrounding country, we seated ourselves for several hours enjoying the beautiful scene which lay like a map spread before us.”

In Honolulu, Albert Peck mentioned going to a sailors’ reading room and library, though described it as ‘the most lonely place in town” where there will “seldom be found more than one person in it, and often none.” Unlike the more accessible public houses, this institution was tucked away off the major streets and Albert admitted that “there was no temptation to repeat a visit, for there was nothing readable on the table but a few pamphlets containing reports of societies &c. with a few old papers, and an odd volume of Chambers Edinburgh Journal with no beginning or end.”

Sailors Institute in Honolulu

Some locations whaleships stopped in were not large ports but instead the small islands dotting the ocean expanse. When the Bowditch stopped at Kosrae (called Strong’s Island in Samuel’s journal) to trade for provisions with the native residents, the crew was given liberty. Samuel described what he did with his day:

“Saturday the Starboard wach employed aboard mending Sailes and other Ships duty. the larboard wach has there liberty on Shoar & I hav gest returned from of Shoar having ben ruising all day for Shells on the reef on the other Side of the Island where they r very plenty the reef is a natural curiosid [curiosity] the breakers rool mountains high it extends all around the Island the pashag [passage] for the bay where we lay is very narow but it afords good anchorage when once in So goes the imes with us tiard [tired] as the Devil.”

Cruising for shells! How he may have spent his time in a large port city like Rio de Janeiro that had the draws of entertainment establishments vs a small island in the Pacific however may have differed greatly.

Liberty ashore was ultimately a pressure valve on a dangerous industry and restricted life. Sometimes what that release looked like was destructive and invasive, sometimes it held mutual goodwill and play, and sometimes it was a solo reprieve to reorient oneself to land again. What it looked like for each crew member was as individual as what led them to the work in the first place.